![]()

You know all you have to know about pie charts. And you are likely to hate or love them. But I know you are willing to accept a more balanced approach, and that’s what I’ll attempt to do here. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about and think grown ups loving or hating charts is, well, weird, don’t worry, it’s just for fun. Keep reading.)

Let’s start with a a few stats:

- Google returns 2.2 million pie charts in image search, 1.8 million bar charts and only 0.34 million line charts;

- Percentage of 3D pie charts in the first page: around 30%;

- Percentage of pie charts with exploded slices: around 15%;

- Bad pie charts (3D or exploded slices or legend or too many data points or no labels or unsorted slices): around 99%.

- People love pie charts;

- People love to abuse pie charts;

- People don’t know how to make a pie chart;

- Teach people how to make a pie chart;

- Show them how abusing pie charts can be bad for business;

- Let them decide if they still love pie charts.

What is a pie chart?

The pie is a circular chart used to display proportions of a whole. In the corporate world, market share is the obvious example of data that can be represented with pie charts. You are likely to see a lot of pies in a market research report also.

To make a pie chart your data should consist of:

- Mutually exclusive, non-overlapping categories (a data point cannot belong to more than one slice);

- Collectively exhaustive categories (all data points in the whole must be represented);

- No negative values;

- Same measurement units;

- Categorical variable;

- Categories must be seen as parts of a meaningful whole;

If you haven’t read the page What is a chart I recommend you do it now. I’ll wait.

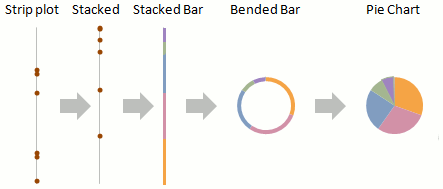

Welcome back. Now you understand the origins of a pie chart:

As you can see, we first map the distances between data points, then stack them, connect them with a thick line (looks like a stacked bar chart), bend them and finally remove the hole to get the pie chart. Don’t forget to color-code each slice.

How do you read a pie chart? Research shows that people compare slices based on one of three measures: length of semi-arcs, angles and slice area:

What can we read here? The first slice accounts for around one third of the whole. Perhaps more interesting, the first two slices account for more than half of the whole.

Criticism

Pie charts are the data visualization expert’s pet peeve. Here are the major arguments against:

- Research tells us that people do a very poor job at measuring angles and semi-arcs and comparing areas. The pie above confirms this: it’s very hard to say which one is the largest slice. Try it for yourself.

- A second argument is that you can’t use many data points. With more than, say, five or six slices the chart becomes overcrowded and even more difficult to read. The more slices the less variation between them, so the harder to compare the arcs/angles/areas.

- A third argument is that is a very low density chart. This means that the real estate needed to display a single data point is excessive. In the space taken by a pie chart with five data points we can easily display a scatter plot with hundreds of data points.

- A fourth argument is that you can’t compare series, for the simple reason that you can’t use more than one. If you want to compare two or more series you have to make two or more pie charts. But if you can hardly compare slices within a pie, using multiple pies is beyond forgiveness.

- Finally, the poor pie digs its own grave when it allows for the level of “creativity” as displayed below:

- Due to a parallax effect, the slice “Pork” seems to be the largest. If you check the pie chart above you’ll see that that’s not the case. And because the chart is “exploded”, it’s even harder to compare angles because they no longer share the same center.

What Experts Say

So, what do experts say about this? Let’s start with Edward Tufte in The Visual Display of Quantitative Information:

A table is nearly always better than a dumb pie chart; the only worse design than a pie chart is several of them, for then the viewer is asked to compare quantities located in spatial disarray both within and between charts (…). Given their low density and failure to order numbers along a visual dimension, pie charts should never be used.

Stephen Few agrees in Show me the Numbers:

(…) allow me to declare with no further delay that I don’t use pie charts, and I strongly recommend that you abandon them as well.

And also in “Save pies for dessert”:

Of all the graphs that play major roles in the lexicon of quantitative communication, however, the pie chart is by far the least effective. Its colorful voice is often heard, but rarely understood. It mumbles when it talks.

Harsh words. Not all experts agree, though. According to Stephen Kosslyn’s Graph Design for the Eye and Mind:

Clearly, we need to temper Edward Tufte’s (1983) assertion (based solely on his intuition, as far as I can tell) that ‘the only worse design than a pie chart is several of them’ (p. 178). In some situations, this opinion is no doubt justified, but we should not make such a sweeping generalization about the value of any type of display, independent of the type of data to be displayed and the purposes to which the display will be put.

What about Ian Spence? He writes a lot about pie charts and the measure of proportions. In “No Humble Pie: The Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart” (PDF) is writes:

In my opinion, much of the adverse criticism of the pie has come from those who have wished it to do more than it could. The pie chart is a simple information graphic whose principal purpose is to show the relationship of a part to the whole. It is, by and large, the wrong choice as an exploratory device, and it is certainly not the correct choice when the graph maker or graph reader has a complicated purpose in mind.

If there is something that I would like to have written about pie graphs it is this “Expert notes” at ManyEyes:

Pie charts have a mixed reputation. They are popular in business and the media but many information designers have criticized the technique. Some claim that the pie slice shape communicates numbers less exactly than other possibilities such as line length. But this remains unclear in the context of proportions: for example, we have seen no studies that looked at the task of judging whether an item is more or less than 50%. It’s also unclear whether exact communication of numeric values is the only evaluation criterion; at least one study indicates that use of a pie chart for analyzing a problem as opposed to a bar chart changes the way people think about the problem.

We are having this discussion since 1926 (when the first scientific paper was published), and it’s not likely it will end soon. So, what’s a poor data analyst to do?

Don’t avoid pie charts, avoid bad questions. Good questions leave no room to pie charts.

Don’t compare chart types. Pie charts are no better than (stacked) bar charts or the other way around. It doesn’t make sense to compare them.

If you are an innocent victim of circumstances (your boss likes and wants pie charts) the best you can do is to improve your pies.

Rescuing Pie Charts

There are no synonyms in data visualization. Using a pie chart is not the same of using a bar chart. The questions are likely to be different because of a fundamental difference: a pie chart is about parts-of-a-whole. And that make a whole difference, so to speak.

Let’s take a look at the pie chart again:

We can see that beef and chicken each account for almost one third of the total. It’s much harder to see that with a bar chart if you don’t look at the axis. On the other hand, in the pie chart you can’t see which one is bigger; that’s much simpler with a bar chart.

Let’s rearrange the slices:

When grouping slices (red meat, poultry and fish and shellfish) we can see that red meat accounts for more than half of the total. That’s something you can’t see in a bar chart. Stephen Few accepts that this is the “secret strength of pies” but he immediately dismisses it as strength that is “rarely if ever useful” and that “the fact remains that a comparison of two sets of summed parts is rare in the real world”. It may be so, but the reason is simple: we passively accept what we get and forget to analyze the data.

Pie charts Do’s and Don’t’s

Don’t use 3D: It should be clear by now that 3D effects significantly distorts the message and should never be used. For examples of what you shouldn’t do, read my post 16 creative pie charts to spice up your next infographic.

Don’t explode your pies: The explode option should be used to call reader’s attention to a slice. Exploding them all doesn’t make sense, because you can’t call reader’s attention to everything. But even exploding a single slice should be avoided. If there is a special slice change its border slightly. The readers will notice.

Don’t use a legend: This is a generic rule, not pie-specific. Don’t force the reader to go back and forth between the legend and the chart. Label the slices directly.

Don’t use too many chunks: Please not that I wrote “chunks” not “slices”. In the pie chart context, a “chunk” is a meaningful group of slices. Let me show you the difference:

The pie chart on the left contains a single chunk, with six slices. The pie on the right still has six slices, but we’ve grouped them into three chunks. Now we can see that red meat accounts for more than half of food availability. You can still read the slices, but now you have a new level of reading. This clearly improves your insights.

Sort the slices: you should always sort the slices from the highest to the lowest value within each chunk.

Gray out small slices: If you have too many slices you don’t really have to create an “Other” slice. Just gray them out. As a general rule, I would gray out slices below 2%. Make sure readers know these slices belong the the “Other” category. If they are not relevant you don’t even have to label them.

Pie Chart Takeaways

- Humans are unable to compare angles and that’s the main scientific reason why you should not use pie charts;

- I have a much more down-to-earth reason: they dumb down your message and they take up too much space for the value it provides;

- If you want to make a pie chart please follow these rules:

- Avoid 3D effects;

- Avoid exploded slices;

- Don’t compare pie charts;

- Label the slices;

- Group slices into meaningful chunks;

- Use a color for each group and a shade for each slice;

- Sort slices within each chunk;

- Mute (gray-out) slices below a predefined threshold (1% or 2%);

Reality is complex and if you try to oversimplify it you’ll fail to understand it. Proportions can be a good starting point, but analyzing a business based on proportions is just lazy.

We cannot underestimate the fact that people are naturally attracted to pie charts. They effortlessly understand the metaphor; they like its colorful simplicity. This comes with a price tag attached. If you make too many pie charts you should be aware of this.

Let a pie chart have a supporting role, but it should never be the protagonist in your story.

References

- Stephen Few: Save pies for Dessert

- Ian Spence: No Humble Pie:The Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart (PDF)

- Robert Kosara: Understanding Pie Charts and In Defense of Pie Charts

- Jon Peltier: I Keep Saying, Use Bar Charts, Not Pies

__________

I’m writing these pages to create a consistent approach to data visualization for Excel users. You can navigate this series using the links on the right.

If you like this page please share it using the buttons below. And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter!

Another great post. Love your 2012 new approach 🙂

Thanks Bernard.Well, it’s not easy. Hope it lasts…

I should caveat my comment, that I am in the ‘never use a pie chart’ camp (evidenced by one of my more popular blog posts, titled simply ‘death to pie charts’). And while I plan to remain in that camp, you present is a well written and well balanced post. Nicely done!

Hi Cole, thanks. I like to play the devil’s advocate from time to time…

I do not think that the origin is correct. I would say, that a pie chart is simply a stacked bar chart in polar coordinates. That’s all…

The rest is a nice job! Cool.

Stefan: And what is a stacked bar chart? Stacked data points in a Cartesian space.I believe you don’t like the “bending” thing. This is a transformation from Cartesian to polar coordinates.Doesn’t change the process, just explains it better. Thanks for that!

Pie & Parfait.

This example is one where I’d present a combination chart. The pie canbe accompanied by a parfait — a stacked bar chart.

Your chunk of red meat, showing the majority, would be in the pie, where the two (no more than three) slices show the majority preferences or factors. The remaining minority elements are all show in one color– exploded — slice, linked to a rank ordered (top is the least rank, bottom the highest rank) stacked bar chart. This bar would show the (four or so) constituent factors and even shows the weight of each factor, but illustrates that even the biggest such “other” factor is a piece of the smallest slice.

i’m still not convinced. you could more easily convey the message in a table as tufte suggests with sub-totals for red meat, poultry and seafood. i have yet to see a convincing reason for a pie chart.

Great summary of the pie chart debate from a practical point of view.

Looking forward to the next articles in this series!

Plum Pie Primers (& parfait)

For Marc-Paul.

Any chart is illustrating a story. I know of two stories for which the pie has useful attributes. Let me discuss the attributes and then the stories. I may not convince anyone but it helps clear my own mind.

Even though audiences generally lack the ability to distinguish differences between near-similar angles, an exception to that general truth arises with perpendiculars. A pie chart oriented to a page or presentation screen with right angle corners reaches an audience surprisingly adept at identifying true vertical lines from those slightly out-of-plumb. The audience can also in that case distinguish between true horizontals versus lines at a slight slope. A pie chart with one true vertical radius – big hand on the clock face “twelve” , as above between beef and shellfish – clearly implies an invisible reference grid denoting quadrants.

Even though audiences are bad at distinguishing shapes, many are even worse at doing arithmetic. The table method may often distract from the intended message as people struggle to add up three or so two digit numbers and come up with the same sum more than once. I’ve seen some people, confronted with a table and sub-table, attempt to add the sub-totals back in to the data (as if, above, a person added “beef” and “pork” AND “red meat”.) And finally, when I’m attempting to convey both raw data and the percentages, some people seem to find the number of numbers in a table of tables just all too much. “Is that twenty nine percent of the 321 people in the survey or are you staying it’s 29% of the 93 people who answered that question?” (Obviously it rarely occurs to such an audience that 93/321 _IS_ 29%)

So the best attributes of a pie chart are allowing the slice / shape to portray a fraction (in comparison not to other slices but compared to a fourth, a half, or three-quarters) and the data label to show the raw number.

So where do these feature best tell a story? Two places. One is majority preference. The other is in introducing or transitioning from introductory data concepts to a Pareto chart.

The first story uses the “plumb line” feature of the pie — the plum pie. Orienting the one (sometimes two) big(gest) slice(s) to the left shows whether or not the data represents a majority. THAT, the magical majority number, is the number of interest. It’s the time when the “portion” is more significant than the number. Whether or not the slice arc is 1 or 2 or 4 or any few degrees more or less than 50 is less important than that the line is in that vicinity. All the other smaller data elements can be shown as one slice to the right which is linked to the “parfait” stacked bar chart. That itself is rank ordered, biggest element on the bottom. The scale of the bar should show the fraction and the data label show the actual count or measure of the elements. (This because we agree the measure is most often more interesting than the fraction-of-measures) If the big pie slice shows the desirable more-than-majority very few audiences will look at the parfait. If the big slice is just short of a majority then one or more layers of parfait –that might be peeled out and added into the pie reciepe — become object of somewhat intense scrutiny.

The second story is a transitional chapter in the larger story of Pareto Analysis. If your audience does not yet easily “get” the 80/20 rule, the more-than-three-quarters pie chart is the way to introduce the idea. The more traditional Pareto chart shows an accumulation line rising to the right across the top and the “slice” data as ranked vertical bars stair-stepping down left to right. Obvious — AFTER the third or fourth exposure. But to begin it’s handy to show that a SIGNIFICANT FEW big slices (again to the left) suck up MORE than three-quarters (about 80%, in fact) of the pie. Then there’s the small “other” slice linked to the parfait of “everything else” on the right. The everything else parfait is there to illustrate that no idea / factor any audience member ever contributed has been ignored — it may be the scum on the top, but it’s in the mix. But the pie is about the few big slices clearly measured and representing more-than-75% — to an audience that’s never heard of Pareto. It’s a useful primer.

That said, the twenty percent of the audiences who matter will be competent with arithmetic and the Pareto Principle for much more than 80% of the narratives a chArtist migh be called upon to illustrate. The need for pie charts should be rare. But as limited as they are, for a limited set of purposes, such needs are well matched to the paired plum pies and parfait.

after reading this article and the comments of Pouncer … both very interesting I thought of a pie chart that revealed a data on the other … I have made dynamic pie chart from groupped data based on active cell … The idea seemed good … so I issued a challenge:

https://sites.google.com/site/e90e50fx/home/Huge-challenge-2-Dynamic-Pie-Chart-from-groupped-data-based-on-active-cell-without-VBA-without-support-cells

… tomorrow will publish my solution

best regards

r

I confess to being guilty of creating one of the much maligned pie charts – in fact it was a pie born out of a slice of another pie no less (https://dl.dropbox.com/u/39132997/Capture.PNG). I need to update the publication this appears in with new data but the pie born of a slice visual still seems rather seductive to me. I’m just wondering what alternatives you’d recommend in this instance. Thanks for your thoughts!

Hi Dave,

I’m crushed that I failed to persuade you to try the plum-pie-&-parfait receipe above.

Your data portions are interesting in that you clearly have a super-majority in the primary pie (66/33) but no majority at all in the secondary pie (48/21/20/11) I assume you have unusual need to draw a clear distinction “very well” and “well” in the subset. Given that, I think I’d use a tall, thin, stacked bar on the far left of the chart, 66 on the bottom and 33 on top. Then your “exploding lines” out to the pie, big and centered. The pie diameter would just short of the height of the bar; indicating the relative importance of the two datasets. The top edge of the pie would be even with the top of the bar and the lower edge would “float” above the bottom reference, to remind viewers it reprsents an extract or sub-set.

I’d orient your pie such that the “very well” near-majority (48) slice started at the six-o’clock position and swept up on the left to nearly the twelve-o’clock. I’d make it green (not blue) as a “no problem” condition. The “well” faction (21) would be the turquoise (semi-green) slice running back from six-o’clock toward three-o’clock. This is also near the bottom implying sort of a “base” condition. The largest problem slice would be “not well” (20), and be a yellow slice around three-o’clock. And the most pressing, though smaller, “not at all” slice would take prominence near the top, around two-o’clock, in red.

Any text commentary about the situation would have “headline” text near the small red slice and smaller supporting text running down from there. Your overall layout leaves the tall bar in about the left fourth of the page, the pie with half all space in the middle, and the right hand fourth column for text and discussion.

The one percent (speak other language) in your left pie is not clear. If it’s important you might consider re-labling to indicate whether this is “Spanish-and-other-but-the-other-isn’t-English”, or “English-and-other-but-not-Spanish”, or “one-or-more-languages-neither-of-which-is-either-Spanish-nor-English” And if there might be a local majority (0.5% among all others: Phillipino-Hispanics speaking Tagalog? Brazillian “Hispanics” speaking Portuguese? ) why not call it out?