A new data visualization research paper finds that chart junk does not harm accuracy and actually improves recall. The paper is an interesting read but, unfortunately, not for the right reasons.

I’ll discuss the paper in an upcoming post. Today I just want to comment a sentence from the introduction:

“This minimalist [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][Tufte’s] perspective advocates plain and simple charts that maximize the proportion of data-ink – or the ink in the chart used to represent data.”

Now, let’s see what the authors believe to be a minimalist chart:

This is not a minimalist chart. It may be a plain and simple chart, but it’s also an ugly one. No wonder no one remembers it.

You see, when you strip a chart down to its basic features, a real minimalist chart also plays with variables like color to emphasize / de-emphasize the remaining features (series, grid lines, labels) to create an aesthetically pleasing experience that drives an emotional response. And that’s what the authors themselves do when reporting the results:

This is a fairly Tufte-compliant chart…

Problem is, if you misrepresent a concept it undermines the entire research. Instead of “minimalist” charts, the authors should call them what they really are: placebo charts. So, they should say: “In our comparison between junk charts with a low number of data points and placebo charts, the results suggest that…”

A note about data-ink ratio. I believe that the deep meaning of the data-ink ratio is not to remove junk, but to create more complex and insightful charts. Once you remove useless “features” you get more chart real estate and you can add more data (Tufte says: “to clarify, add detail”). And that’s how you really maximize the data-ink ratio, not just because you remove junk.

So, what do you thing? Are minimalist chart just some boring plain & simple charts or there is more about them than these authors are willing to accept?[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Jorge,

I found the link to your post from @Jon_Peltier right after I responded to @joemako for commenting on my blog. Joe showed an Edward Tufte “minimalist” alternate take on a bullet graph inspired New York Times data visualization and it works at showing many data points easily.

Back to your blog post. So, you wanted to know what I think? Well, since I have all four of my Edward Tufte books open on my coffee table, I am prepared. Your questions is, “Are minimalist chart just some boring plain & simple charts or there is more about them than these authors are willing to accept?”

I will start my response with this quote from Edward Tufte. He opens Chapter 4, Data-Ink and Graphical Redesign, in his 2001 book, “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information – Second Edition” with “Data graphics should draw the viewer’s attention to the sense and substance of the data, not to something else. The data graphical from should present the quantitative contents. Occasionally artfulness of design makes a graphic worthy of the Museum of Modern Art, but essentially statistical graphics are instruments to help people reason about quantitative information.” The authors of the research listed this book in their references. However, their sample business charts do not match what Edward Tufte spoke of in this quote, in his 1-day class or in any of his four books. Additionally, the researchers should have read Stephen Few’s 2004 book “Show Me the Numbers – Designing Tables and Graphs to Enlighten” and Naomi Robbins 2004 book “Creating More Effective Graphs.” I think they would have helped them understand what business charts and graphs are all about.

Most of what Tufte shows in his books as good examples are not “minimalist.” In fact, Edward Tufte says the best statistical graphic ever drawn is a map by Charles Joseph Minard. It portrays the losses suffered by Napoleon’s army in the Russian campaign of 1812. A small image of it can be found at his website – http://www.edwardtufte.com/tufte/graphics/poster_OrigMinard.gif

There is nothing “minimalist” in this data visualization.

I wonder what the authors of this study would say about business dashboards built based on the concepts of Tufte, Few and Robbins. The amount of data packed into small spaces is anything but minimalist.

In conclusion, there is more about the so called “minimalist” charts than these authors are willing to accept.

@dmgerbino

David: Tufte’s books are great coffee table books 🙂 Funny thing: Tufte uses minimalism (the art movement) as a general framework for his own data visualization theory but refuses to accept that aesthetics play a relevant role in his design options (because he wants to “sell” his theory as an absolute true and the only serious data visualization perspective).

It would be worthwhile replicating the experiment conducted by the authors on your blog. Off course the minimalist charts used by the authors would be need to be replaced with the aesthetically better ones. It would be great to verify both near term recall as well as recall after a few days.

Jorge, I’m interested in reading your critique of the paper.

IMO the problem with Tuftean (tuftist?) principles is that they are not as universal as they sound. In some contexts, say, an annual report, the charts should be able to support the scrutiny of the reader and ask any question on the data they represent with ease. In this case any effort spent on decoration is likely to be counter-productive – one should rather stick to textbook methods.

But in other cases, say, advocacy, the charts are rather used to support an opinion. In that case the author of the chart shouldn’t encourage their readers to question the data, but instead they would like them to take the chart at face value and embrace their own views. Now in that case, adding illustration to the chart helps to drive the message and also helps in preventing unwanted interpretations of the chart.

another thing. Tufte and followers are not opposed to aesthetics. There’s beauty in simplicity yet achieving that beauty is not trivial (typography, choice of colours, layout…) conversely when illustration can help it doesn’t mean that basic data presentation principles should be forgotten. in the paper the examples are from very experienced designers.

I agree that their comparison charts are ugly, but that doesn’t mean they’re not minimalist. The authors may have misunderstood the data-ink-ratio argument and thought that the less ink the better (i.e., no filled areas), but that’s clearly not true. A few simple changes would have made those charts nicer to look at; but easier to remember? I doubt it. They would still all look the same. And even if you introduce arbitrary differences, there is no connection between a different color scale, slightly different layout, etc., and a particular type of data.

So while I agree that they could be improved, I don’t think it takes away anything from their findings. I also agree with Jerome that you have to take the use of a chart into account. We don’t generally accept universal rules that apply independently of context, so why should we think that Tufte’s ideas apply everywhere without exception? Good, thoughtfully designed, embellished charts and infographics clearly have their place.

I also think the study misses the mark. My concept of chart junk more revolves around unnecessary gridlines, 3D rotations, and so on, rather than a theme to the chart. This is epitomized in their paper – for example Figure 3 – a monster themed, but pretty readable bar chart, to Figure 10 – their suggestion of a middle ground of embellishment – ugly, and in the case of the bottommost chart, completely unreadable.

Not every publication wants the clear bar chart style of the Economist – I get that. No surprise that a line chart that follows the curve of the leg of a showgirl (while still easy to read) is more memorable than a plain line chart.

Careful, appropriate embellishment, that adds to the feel, but does not hide or obfuscate the message is key.

Robert: I am not in the exegesis business, so I can’t tell you how we should read Tufte, but I believe that Tufte’s minimalism is basically Mies van der Rohe’s minimalism applied to data visualization. This provides a consistent framework from where Tufte’s data visualization principles are derived. The difference between minimalism and “plain and simple” is that there is an aesthetic dimension that is missing from the “plain and simple” charts.

Does it matter? I think it does, but it wouldn’t change the results much. But that’s a different story. I’ll discuss that in my next post.

Jerome: Obviously Tufte wants to sell his principles as “universal”. His principles are a revelation, not something open to discussion. And they actually work very well within a positivist framework. As soon as you add emotion to the equation (and you often need to do that) Tufte’s principles start to look way less universal.

No, Tufte is not opposed to aethetics. On the contrary, he embraces (an then denies) it.

Alex: Well, figure 10 is an unacceptable chart in a data visualization paper…

Paresh: I would love to conduct some kind of experiment, but I wouldn’t ever do it in an artificial environment. I would do it with users using their data for their daily tasks.

My take on the meaning of the “data/ink ratio” is to consider whether the ink used is showing data or not, rather than trying to reduce the quantity of ink in all possible ways.

With a filled bar (using lots of ink) the ink is there to show the data, and nothing else, and meets this criterion.

Gridlines, 3D effects and so on are not specifically showing the data and should be removed in most cases.

Arguably, lighter shades for gridlines, axes, labels, and even the fill colour of a data bar also reduces ink used while showing the data effectively.

Removing the fill from a bar and showing an outline is missing the point. Reducing the ink on the page is not the intention of Tufte’s method (or other proponents of good visualisation, such as Stephen Few). They are not going for an economy drive to spend less on ink, but argue that no ink should be on the page which does not directly help to display the data.

A true minimalist outline bar needs no vertical lines, since they do not directly show the data, only a top line is needed. And a minimalist top line is a point, so should we only use dot plots? Other way round – the top line is only enclosing the white space, it is the length of the vertical line which encodes the data, so lose all the width and have a single vertical line instead. Clearly in both absurd cases this extremist view does not help people to actually see the data – a filled bar (with no outline) is simpler bolder and easier to perceive.

The data/ink ratio question should be “does all the ink I used help to show the data?”, not “can I show this data using even less ink?” and in this sense it is not a pure minimalist approach, but a pragmatic one.

From the perspective of a total chart n00b (who, coincidentally just read some Tufte):

Data/Ink ratio is probably meant as a baseline – something to remind you on where to start. The bare minimum to communicate what is you’re trying to say. Additions past that should probably:

1. Not interfere with or distort the data being presented

2. Not distract from the data being presented.

So I’ve been under the impression that the whole data to ink thing was more like a ‘best practice’ rather than some hard and fast rule. But again, I could be totally wrong on this.

Not that I have any business commenting on this in my noobishness, but the only ‘pretty chart’ in that paper I thought wasn’t so hot was the “diamonds are a girls best friend” thing. It was the fact that the plot area breaks right in the center which caused me to have to think about it for an extra moment. That, I kinda think is a bad thing, but it might be a difference: my reasoning for learning charting is to show bosses at work a whole lot of information a whole lot of fast. The guy who made that might have had something different in mind.

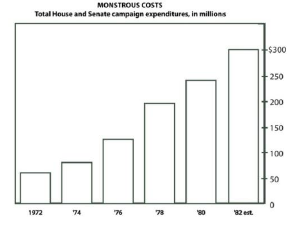

The study is comparing the mosquitos-killing efficacy of sledgehammers v. flyswatters. For a graph with six data points, nearly any approach would work (even a pie!). For the presented cases, graphs are altogether unnecessary; a table or sentence would suffice: “Total House and Senate campaign expenditures increased from ~$50 to ~$300 million from 1972 to 1982!”

A more suitable visualization for any of these tiny data sets would be a sparkline, i.e. a word-sized graph. Effective design does not involve constructing vacuous and sprawling graphs (even well-formatted ones that make good use of color) to present virtually no data. Certain design principles are valued because they facilitate pattern-recognition and information processing among large quantities of data. Using Holmes-like embellishments to represent multiple data series with hundreds or thousands of data points would fail. This would be evident if the study took the opposite approach, namely selected exemplary data-rich graphs and converted them to Holmes-style graphs.

The article demonstrates that visual embellishments are more effective at marketing, i.e. having folks take notice and remember your message. (However, the study is based on 20 subjects, so I would be reluctant to draw even that conclusion.) If marketing is your goal, it’s no surprise that minimalist charts are not the best medium. Most of my work involves trying to makes sense of large quantities of complex, multidimensional data. And for that, I prefer not to use flyswatters.