Great data visualization is hard to measure: you can’t prove you have a good chart. Unless you can convince your employer to deploy at least two different formats/layouts and are able to compare results, you can say “this is a good chart” but that’s an act of faith, not an act of science.

It’s True Because It Rhymes

Information visualization experts like to evaluate a chart based on its compliance to some more or less accepted standards (Tufte’s data-ink ratio, for example). That’s like saying “it must be true because it rhymes”: the truth is defined by the language itself, not by the real world. Now, please close the curtains of our ivory tower…

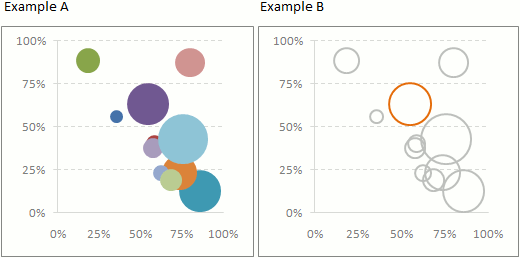

I know, it’s not easy to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of good displays. They look natural and obvious, undeserving of praise and, probably, boring and uninspiring. Compare these charts:

This is a true story: users wanted to evaluate sales territories, one at a time. Color-coding each bubble (Example A) was pointless, while Example B provided context without distractions. Guess what chart they would choose if they were allowed to… (happy ending: they reluctantly accepted Example B). (A word of advice: if you are looking for a promotion, a kindergarten chart variety always outperforms a “serious” chart.)

If your chart is doing a good job at helping people, no one will actually be aware of the chart’s role at making sense of the data. That’s why it is so hard to find good examples of data visualization using standard charts. If people actually like them, they like them because of their usability and/or interactive features.

When Stephen Few asks the readers “true stories about the benefits of data visualization” that’s almost an admission of impotence. He should have hundreds if not thousands of good examples to share with us, right? Well, I know there are many examples out there, but I can give you none, sorry. Is data visualization some kind of astrology? I know it works. Why? Because I have faith. (On second thought, he is not asking for good data visualization examples. It really doesn’t matter if you use Tableau or Xcelsius, and that’s a relief.)

Opening the Pandora Box

Ultimately, what makes a good chart is how it resonates with your audience. Assuming that your are not unethically distorting the data, a chart that forces people to act is better than another one that only makes people aware of the subject.

If a single chart can save the world, it will not be a Few’s or Tufte’s 100% compliant chart. It will be a glossy Xcelsius pie chart.

(Wow, that’s depressing…)

If you read this blog that’s a clear sign of intelligence and sophistication 🙂 . Unfortunately, you are not representative of the typical data visualization user and/or producer. The real world loves pie charts and doesn’t understand scatter plots.

Here is my Pandora box: give the audience what it expects and understands, even if that hurts your data visualization soul (OK, give it 90% of what it expects and use the remaining 10% to educate it.)

Cultural Relativism? Not So Fast.

Please don’t misrepresent these arguments. I’m not saying that all charts are born equal. There is a reference point and some misconceptions should be avoided A chart that maximizes insights, removes clutter, uses color wisely and clearly shows the patterns hidden in vast amounts of data, that’s probably a good chart and that’s what you should aim for. And yes, you should avoid pie charts.

If you present some sophisticated charts to your unsophisticated audience you’ll lose it. Relax. Draw a line but don’t forget the candies. You can take a horse to the water, but you can’t make him drink, unless you give him some sugar cubes…

Thank you! Finally some one who operates in the real world. Why Tufte and Few are right in talking about the excesses in charts (3D bars anyone), their off base in their ivy-towered pretentiousness of what is good. Most of the presentation I make are to people (boards for example) who have little knowledge of the subject matter and little time to study a chart. They need something they can comprehend quickly–limit the chart candy. And I need something that can hold their attention for 45 seconds–make it interesting–something Tufte and Few forget. I am not publishing something for The Royal Economic Society

very well stated. The medium (colors and whiz bang) should never distract from the message. And correctly to your point a lot of people are looking for attention, thus showing off with the tools instead of getting the job done.

The best mediums convey meaning without drawing attention to themselves. The economist has excellent chart design that in an english sense doesn’t draw attention to itself, it just performs. That is of course with the exception of the horrific “year in 2010” and other year in Economist publications. These year end predicotorama feast appear to be the handy work of USA today chart makers on a ritalin binge. 🙂 Novelty and trite tricks attract attention, consistent quality endures.

Jorge, I was at visweek this month and was debating a similar topic: can visualization change the world? there are quite a few examples were a visualization was interesting, thought-provoking, etc. but I don’t think that the discipline has lived to its potential, because it’s not used enough. there are tons of people out there, especially in businesses, who could benefit from insights gained from better visual practices. Such techniques are gaining ground, however, because of the availability of new tools and more data. At last year’s visweek, the CEO of tableau gave a keynote speak titled “Practical applications of visual analytics: On the cusp of widespread adoption”. I see this happening in 2010.

I did meet Stephen Few over there and asked him if he had gathered any good stories, and was disappointed that he hadn’t. That doesn’t mean that visualization is not useful, but that, again, it’s not used enough.

PragmaticCynic: Tufte says “If the statistics are boring, then you’ve got the wrong numbers”. It’s not that simple. His (and Few’s) approach to information visualization partially fails because people’s emotions are removed from the equation.

Nick: I like to think that a good chart, like a good design, is invisible. Unfortunately, we don’t always recognize how important some invisible things are…

Jerome: most people don’t even know what “data visualization” means! On the other hand, they think they know what a chart is. And they know how to make one in Excel. That’s our starting point. Discussing “working memory”, “data-ink ratios” or (God forbid) “using color preattentively” is, not only boring, but also pointless. First stop: “let’s make some simple adjustments to show how they help you to understand your data better”. (To teach someone to ride the data visualization bicycle we need training wheels). Yes, visualization can change the world. One user at a time. At this rate, 2010 is perhaps too optimistic…

Jorge, I totally agree with your pragmatic view on the usefulness of data vizualisation. In my opinion, the current business lack of adoption of dataviz best-practices is mainly due to 2 elements:

* dataviz best-practices not being part of your standard school/graduation curriculum

* user-brain formating based on defaults options in software and exposure to a small set of standard graphics in both press/tv media

Trying to prove the usefulness of a more sophisticated representation is a lot of work because it implies trying to change the mindset of the reader. Most of the time it’s a long process… but for those few situations where you hit spot on with a “best practice” approach that appeals to the leader of the organization.

Just a quick note of hope: since I’ve started reading Jorge’s blog (and others of the kind) I’ve started to implement some of the good advices that I’ve found. Slowly, obviously.

So, what started to be a numerical monthly report, w/ almost no visualization – good or bad – is now almost completely revised. We can actually look at the report and identify some trends…

Sadly, this has taken about a year 😀 But, it has made by job easier and it has made it easier to get my proposals accepted by my Manager (who is open minded in what regards this changes).

For a room full of people and/or the board, I still go with flashy charts (awful pie charts, colored, and with no real use). It is, has you have well said, all about getting their attention and make them accept our message… 😉

Personally, I’ve received a great deal of value from both Excel, Tableau and the combination of using Excel as a poor-man’s data warehouse in conjunction with Tableau.

I find 3D charts very annoying, always have. I think Few makes very good points about what is good and what is not so good. As this market develops and people have better understand of the differences between simple data visualization and the ability to rapidly probe large data sets, I think people will see the value in tools like Tableau.

Keep up the good work on this blog. I enjoy reading it. Thought provoking and practical.

This a solid pragmatic and prosaic piece. The person communicating should not blame those who are receivers … there is no control there. You need to re-evaluate how you are communicating and connect to the audience. I like data and stats and more complex charts – most people don’t. If I lose them, I’ve missed my objective. Simple as that. Know thy audience and what they can comprehend and digest.

Jorge,

Although I appreciate your blog, I believe that in an effort to be provocative you sometimes stray from the facts. You have done so in this particular post.

You wrote: “When Stephen Few asks the readers “true stories about the benefits of data visualization” that’s almost an admission of impotence.” Not at all. The effectiveness of data visualization is well established by a large body of empirical evidence. My request for “true stories about the benefits of data visualization” was an attempt to get people to share their real-world successes with others. People have told me many real-world success stories, but I have never bothered to record them, and therefore can never manage to remember them in detail.

You wrote: “If a single chart can save the world, it will not be a Few’s or Tufte’s 100% compliant chart. It will be a glossy Xcelsius pie chart.” Didn’t you mean to say “It will “not” be a glossy Xcelsius pie chart”? Based on your later statement about pie charts, I suspect that you did. I agree that if a single chart could save the world, it certainly doesn’t need to be 100% compliant with the principles that I teach, but you said that “it will not.” You’re being provocative in a way that could backfire on you and any of us who try to help people use data visualization effectively. There are a great many software vendors out there producing really ineffective products that love any opportunity they can get to promote their bad products. They love statements like yours and will take them out of context to serve their own interests in ways that will harm the people who need good data visualization tools.

You ended with the statement: “Draw a line but don’t forget the candies. You can take a horse to the water, but you can’t make him drink, unless you give him some sugar cubes.” Horses that are thirsty don’t need to be tempted with candy. Pure water running freshly in a stream is what they want. People that aren’t thirsty might need to be tempted with something sweet, but you don’t give them candy instead of water, you give them candy to get them to then drink the water. You seem to be suggesting something about my work that you’ve suggested in the past–that I oppose charts that are delightful in appearance or interactive. You know better than this. The “eye-candy” and interactivity that I oppose is only that which undermines the objectives of the chart. Beauty and enjoyment need not be at odds with effectiveness. People who create charts that incorporate decoration and motion in ways that undermine meaning, distract from the message, or that make the charts difficult to understand are unskilled designers. Do you believe otherwise?

To your reader PragmaticCynic, who commented above, I’d like to say that you must not be familiar with my work. “Ivy-towered pretentiousness of what is good”? You won’t find any examples of this in my work. If you believe otherwise, I invite you to share them. My work seeks to help people like you who present information to those who have “little time to study a chart.” What I teach is extremely simple and practical. It is designed to “hold their attention” and “make it interesting” in ways that engage them with the data. This is something that, contrary to your claim, I never forget. Anyone who knows my work knows that I don’t teach lofty techniques that are designed for “The Royal Economic Society.” You are mistaken.

And finally, Jorge, you not only failed to correct Pragmatic Cynic’s errors, you actually fueled them by saying that my “approach to information visualization partially fails because people’s emotions are removed from the equation.” I do not discount people’s emotions. I am well aware of them and the ways that they can both enhance and undermine the effectiveness of data visualization. If you believe otherwise, as you suggest, then you should support your claim with concrete examples.

I think what Stephen is trying to get at here is that you need to have some legitimate grounding for an envisioned sense of “candies.” Poor expressions interpret candies as extra colors and swooshy animation that more often than not simply add distraction from the task at hand. I think your ratio is a bit off too. We need to educate through evidence, and, as those studies grow, as proper evaluation methods are established akin to the field of usability, the formerly uneducated will be disappointed it came so late. Take some time to read legitimate studies in this realm, often referred to as information aesthetics. Andrew Vande Moere from the University of Sydney is one of few slowly making headway (“Towards a Model of Information Aesthetics in Information Visualization” is a good place to start.) Still, though recorded evidence is elusive, we need to at least build a proper mental model and common vocabulary for the aesthetic principles so we can consistently, systematically respond to requests to ‘spice things up a bit’.

Thanks man … i like your post … so true … especially the lines on Few … indeed it is very difficult to educate people to the DataViz area and to demonstrate the add value in regular BI projects … for the moment they do not want spend a $ on this … for the moment … i think it will change …

Take care

Stéphane

Jorge,

Fantastic. I’m working for 13 years in visualization and for about 6 years with actual customers in software visualization (also as co-founder of a softvis tools start-up company). My experience with the real world, stakeholders as I like to call them instead of the overloaded word ‘users’, is precisely what you describe. Simple graphics, and graphics which _motivate_ their audience to do something about them, work best. Scatterplots, treemaps, parallel coordinates didn’t in so many cases I was involved in. I found a striking parallel between the notions of value and non-value in visualization and the notions of value and waste in lean software engineering (see Poppendieck, 2006), reflected so well in the words of so many actual customers who told me/us: “OK, nice image; nice tool; how much can this save me and/or how much can I gain with it, and what is the price I have to pay for using it?” Sounded like a brutal question first, but I’m afraid they were right. If we cannot quantify the value (and cost) of a technical tool, it’s not a technical tool, but something else. If you’re curious, see http://www.cs.rug.nl/~alext/PAPERS/IEEESW10/paper.pdf

Kind of a far-off comparison (“true because it rhymes”) but I get it.

The A/B comparison touches upon a kind of false test that I think is common. I don’t know if there’s a name for it. But:

* Imagine you give someone the choice between A and B. They will choose A even though it’s wrong. BUT, given the choice among 50 charts, A_1 through A_49 look like A. They will choose B, the correct choice.

It’s kind of a Warhol principle but in a good way….

Another story that comes to mind is the chairman of Sony in the late 70’s. Walk-man’s did terribly in focus groups. Probably they were posing a wrong question like, “Could you see yourself using this?” or “Would you recommend this to your friends?” after having some people sit around a conference table and listen to a corporate tape. They didn’t put people in a realistic situation and ask the question, they just … posed the question.

Does that make sense?

Also reminds me of bassists and drummers. Nobody picks out a well-harmonized bassline or standard-but-perfect drum accompaniment. But oftentimes that is what’s making the song, not the flashy front-(wo)man.

(For which, see Ponytail.)

check out Discovery Exhibition: collecting visualization success stories (visweek 2011) http://www.discoveryexhibition.org/pmwiki.php